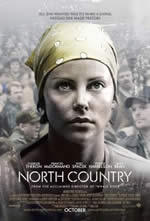

North Country

It starts out where Five Easy Pieces leaves off; you can practically see Nicholson jumping into that logging rig at the gas station as Theron pulls in to fill up. Every ensuing cut invites comparisons to America's early Seventies New Wave, the expectation being that the oil derricks would be replaced with another landscape right out of Bernd and Hilla Becher's imagination: the modern mining complex with its gargantuan, noisy machinery and the cratered wasteland it creates. The impersonal, industrial vista, frozen like space, creates a harsh background to a bleak story of brutal misogyny and domestic violence.

It starts out where Five Easy Pieces leaves off; you can practically see Nicholson jumping into that logging rig at the gas station as Theron pulls in to fill up. Every ensuing cut invites comparisons to America's early Seventies New Wave, the expectation being that the oil derricks would be replaced with another landscape right out of Bernd and Hilla Becher's imagination: the modern mining complex with its gargantuan, noisy machinery and the cratered wasteland it creates. The impersonal, industrial vista, frozen like space, creates a harsh background to a bleak story of brutal misogyny and domestic violence.These traits hold for the first third of the film. The cuts are quick and the camera never lingers, except for a few beautiful, towering crane and helicopter shots across the mining factory and its surrounding quarries. Charlize Theron comes off as a believably beautiful Minnesotan, never exaggerating an accent she hasn't quite mastered, or attempt some untenable level of working class authenticity. There's an absurd naturalism about her character as she develops a political consciousness, an observant naive. The representations of the work itself are unsettling and painful; the women in the cast, led by Frances McDormand as a union rep and truck driver, lend themselves to cultivating a culture of work and home that's entirely believable in much the same way Bruce Springsteen's Nebraska is ghoulish and real. Unfortunately the entire film isn't staged at the mine, in the home, or at the bar.

To the film's credit, it isn't simply the unencumbered, Updikean fantasy land of Five Easy Pieces where the man is somehow the real victim and the woman is a sexless harpy determined to anchor him at home with his family. Nor does this keep the film from taking on deeply existential qualities; one might argue that films about work and prison are probably more "existential" than those of aimless ennui. Although this aspect is muted and ultimately deleted by the courtroom drama unfolding behind each of these flashbacks, it's worth noting that it provides ample opportunity for a fantastic cast to exercise gritty dramas in the home and workplace. However, as the past reaches the present, the film looses it's seamlessness between now and then. Unlike The Sweet Hereafter, the legal drama isn't personal in quite the same way in terms of detachment and loss, and it emerges as a jarring eruption in an otherwise gripping story.

Maybe that's the Hollywood stranglehold at work. Is it possible that even stories that have audiences applauding progressive politics and small novelists are indelibly compromised by their adaptations? Characters like Bill White are just cowboys in white hats and these sorts of paternalistic, even when well-intentioned, progressive and sensitive Gary Coopers come off like chauvinists in spite of themselves. As the film winds down and the conclusion becomes obvious, the sheer momentum is obnoxious and insulting to even sympathetic sensibilities. There's still something not quite right about these message/issue pictures even if they're maybe as close to the genuine article (a reification and bit of wish-fulfillment if I've ever formulated any) as it gets? If that's true, then maybe the artistry that's been heralded in big budget productions has been dramatically overstated.

The sense of film history exhibited in North Country comes as a stinging indictment of its pat conclusion and mechanical progress. There's a real story to be told, but this wasn't it. The story's more in the struggle and less in the temporary and hermetic "victories" presented.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home