Stranger than Fiction: Good Night, And Good Luck.

A film that proved fresh and exciting because it feels like fiction. As Anderson Cooper skulks in the desert, dragging the Vanderbilt fortune behind him somehow plays like cinema verite. With the post-Network era of infotainment so engrained in our epistemic reflex that local and national no longer registers as inane and asinine commentary or pleasant fictions more likely opposite the truth, ushering in a reality reduced to simulacra: the shared experiences remembered through bizarre anecdotes of cultural memory littering our psyche with the sort of useless knowledge helpful solely for Quizzo and Google searches. We've reached a societal disconnect that transgresses escapism and blunders fecklessly past citizenship into the new, weird Americana that represents the country's international reputation.

A film that proved fresh and exciting because it feels like fiction. As Anderson Cooper skulks in the desert, dragging the Vanderbilt fortune behind him somehow plays like cinema verite. With the post-Network era of infotainment so engrained in our epistemic reflex that local and national no longer registers as inane and asinine commentary or pleasant fictions more likely opposite the truth, ushering in a reality reduced to simulacra: the shared experiences remembered through bizarre anecdotes of cultural memory littering our psyche with the sort of useless knowledge helpful solely for Quizzo and Google searches. We've reached a societal disconnect that transgresses escapism and blunders fecklessly past citizenship into the new, weird Americana that represents the country's international reputation.But Good Night and Good Luck doesn't say that, nor does it preach to its audience. Unlike Network, a film that presaged the era of soft news, Good Night and Good Luck comes across as a rote history with no catchphrase to speak of or even cartharsis. In fact, history is presented as it ought to be: an unfolding process, not some triumphal arc replete with the pompous class president speeches leading to easy, ludicrous conclusions. More importantly there is no point in nostalgia; the direct continuum past to present, from McCarthy and Hoover, to COINTELPRO and Hoover, to Ashcroft, Gonzalez and the PATRIOT chorus, there's nothing worth rhapsodizing. Analytically speaking, this is the stuff of a Benjamin aphorism.

David Straithairn's Murrow is breathlessly reserved, forthright and filled with conviction. Opposite him, Clooney plays his equally cool producer, the aptly named Fred Friendly, Clooney being careful to write himself out of St. Peter status as Jesus' footman. The remaining cast offer lovely supporting performances, Jeff Daniels perhaps foremost among them as the stern but fair management man and secret couple Joe and Shirley Wershba playing the skeptics with something to lose.

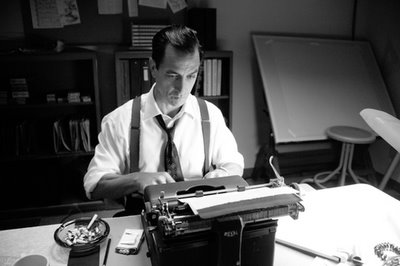

Good Night, and Good Luck. succeeds among biopics for its restraint; at under 90 minutes there's no time for meandering flashbacks that place characters in irrelevant context. The film is present to itself and its subject and leaves out the messianic qualities for which is hagiography's renown. A film so lavishly produced, shot in gorgeous black and white to remind audiences that this isn't some science fiction, gives historic weight and Dianne Reeves plays a jazz singer whose interstitial performances are as much evidence of television's Golden Age as they are the choruses corresponding to each scene in turn.

With message films being the order of the day and so few delivering on their promises, Clooney exceeds expectations. Unlike his predecessor Robert Redford and mentor Steven Soderbergh, Clooney as a writer and director undoes all the things that made HBO's K Street so unbearable. By avoiding cant and cliche and presenting a realistic portrait of an important, but minor historical figure, Clooney has a faith and optimism that perhaps more likeminded people lack. As politicians struggle to define their legacies and shore up support for upcoming elections, films like this one are like quiet cautionary tales instead of morality plays and dumb shows pantomiming to the choir.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home