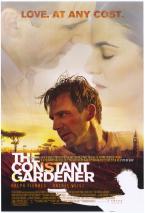

The Constant Gardener

How I thought this would be what Pollack hoped for The Interpreter, plus all the best elements of French Connection II (that's right - the sequel), is beyond me. After they threw in the kitchen sink stylistically, what else was left to be done? Fiennes almost redeems his smash-you-over-the-head (figuratively) performance in Schindler's List. Nevertheless, this has that sort of wish fulfillment that ruins most left-oriented political thrillers. Can't someone be smart enough to let the good guys lose, and badly?

How I thought this would be what Pollack hoped for The Interpreter, plus all the best elements of French Connection II (that's right - the sequel), is beyond me. After they threw in the kitchen sink stylistically, what else was left to be done? Fiennes almost redeems his smash-you-over-the-head (figuratively) performance in Schindler's List. Nevertheless, this has that sort of wish fulfillment that ruins most left-oriented political thrillers. Can't someone be smart enough to let the good guys lose, and badly?See also: Conrad's Heart of Darkness, Nadine Gordimer's The Late Bourgeois World and Coetzee's Waiting for the Barbarians.

----------

Controversial post-vacation edit: Considering how few films actually drew me into the theater (precisely two - Batman Begins [IMAX cut] and The Land of the Dead), there's more to be said of The Constant Gardener. Perhaps it's that the film has much to be said that hasn't yet been said elsewhere, but with all the subtlety of John Q. and its best intentions notwithstanding, this is yet another film adaptation that promotes literacy. Aa good story and bad retelling can be easily identified, and such was the case here. In political films like this, it's often the revelation and naivete that make the difference between patronizing the audience and preaching to the choir, engendering the sort of despair necessary to tie the personal to the political, each in their own inextricability.

That feeling of righteous indignation that becomes brooding anger in films like Z, The Battle of Algiers, The French Connection, Masculin-Feminin and in particular Medium Cool that makes it possible to consider how easily the public can be duped into supporting positions in which it doesn't believe and believing in positions it doesn't support; there's a variety in play here that simply can't be manipulated so didactically. Plenty of people know that pharmaceutical companies are fraudulent, cynical and heartless, but few know the manner in which these corporations go about executing their mendacious schemes tied to profit in the name of health. Truth be told, The Constant Gardener doesn't really tell that story very completely, resorting to vague explanations about suspicious activities, disappearances and questionable testing practices in the global South.

Maybe those other films succeed because they do away with messianic principles and The Constant Gardener clings to them. This is a personal reflection on the character of American and English political thrillers and their notions of heroes and villains, but there was something disgusting in believing that self-righteous European elites and local elites would be the sole actors in the film, reducing a poverty stricken populace to a position of voiceless animals being led to slaughter. As we can see in our current global political circumstance, no amount of intimidation and oppression goes without some degree of public protest. That, and the myriad other plotlines (ethnic/clan violence) that go more or less unexplored depict a place so chaotically banal that it's as though one English diplomat tours Africa with a violent storm of steel tracing his every move.

Absent are all the democratic sensibilities present in City of God, Meirelles' brilliant film about rival gangs in Brazil's underworld. Unlike that film, where good and evil are less clearly and ardently supported, The Constant Gardener fails to investigate the inability to build coalitions around issues like global health and drug testing, choosing instead to rely on the age old instant-sleuth tactic so common among films that treat social justice as something to be adminstered paternalistically rather than reclaimed from their expropriators. That may be my own wish fulfillment betraying me - how can one tell a story if it's not actually happening - but it's my belief that there is far more dissent among indigenous people than is portrayed in the film, a discredit to the subject matter and the people whose lives are at stake.

It will be a curious thing to see how critics receive the film this week. It would be easy to pass it off as a triumph of the liberal imagination, but I fear that would discredit the literary underpinnings that have clearly been done a disservice by the adaptation.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home